The COVID-19 pandemic upended many people’s work lives, relegating office workers to remote workspaces and changing the way people experienced their jobs. Whereas the office setting offered intangible benefits like social support and networking opportunities, those were offset by the greater autonomy and freedom from commuting enjoyed when working from home.

After COVID became endemic, managers struggled with how to successfully bring employees back to the office. “RTW — return to work — was, and maybe still is, the human resource management challenge of this era,” says Joel Brockner, the Phillip Hettleman Professor of Business at Columbia Business School. “Organizations are struggling with it; employees are struggling with it. Nobody’s quite figured it out.”

In 2021, Brockner and his co-author conducted a study to learn more about the conditions under which people re-enter the workplace “with more versus less positive feelings about their jobs,” he says.

Drawing on research from social psychology models, Brockner and his co-author considered the impact of two variables on how employees regard RTW:

- Does employees’ engagement with their jobs change as the RTW date gets closer?

- Does increasing employees’ positive outlook through self-affirmation exercises affect employees’ attitudes toward RTW?

Key takeaways:

- As their RTW dates approached, employees anticipating a return to in-person work more imminently reported feeling more positively about their jobs, in the form of greater engagement and less burnout.

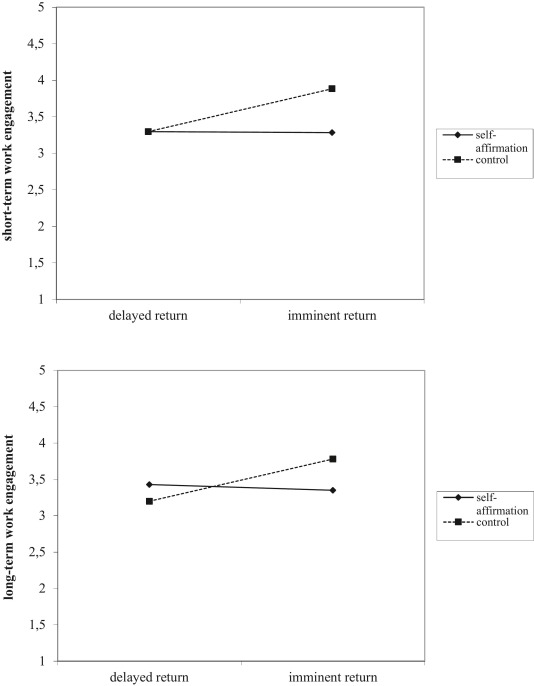

- Surprisingly, engaging in self-affirmation while anticipating the return to in-person work did not produce any positive effects in employees and in some cases was counterproductive. Employees who self-affirmed and who were returning to work imminently reported lower levels of job engagement and higher levels of burnout than those who did not engage in self-affirmation.

- Whereas self-affirmation has been shown to have a variety of positive effects on work-related outcomes in other studies — for example, Brockner and his colleagues found elsewhere that unemployed people who self-affirmed did better in their job searches relative to those who did not self-affirm — self-affirmation is not a one-size-fits-all remedy. Sometimes, less may be more in that those whose return to work was imminent actually reacted more negatively when they self-affirmed relative to when they did not.

How the research was done: The study began in June of 2021, when it appeared that many people were planning to return to work — prior to those plans being upended by the rise of the Delta variant. Over the course of several weeks, the researchers conducted multiple online surveys of employees who were working from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They asked questions about how soon the employees anticipated they were going to return to in-person work and to rate the levels of engagement and burnout they were experiencing. The study defined engagement, which is associated with productivity and worker well-being, as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption.” Burnout, on the other hand, refers to a “negative constellation of work-related beliefs and attitudes” like dysfunctional stress and cynicism.

A week after the initial survey, the researchers asked some participants to engage in a self-affirmation exercise, where they listed and ranked their values and wrote about those that were most important to them. Studies in the field of social psychology have shown self-affirmation to be an effective tool to counter negative workplace experiences. A control group did not self-affirm. Six weeks later, they revisited the survey on engagement and burnout, providing a long-term result, as well.

The researchers hypothesized that workers would have conflicted feelings about RTW and that self-affirmation could help them prepare for the transition. “We went in thinking that self-affirmation would be beneficial,” Brockner says. “It would help people to feel more engaged and less burned out.”

What the researchers found: Over the course of the study, the imminence of returning to work was related positively to work engagement and negatively to burnout. This correlation implied that for workers, the gains associated with RTW (like increased social support) outweighed the losses (like having to commute).

Brockner says this finding could suggest that workers who were returning to work imminently may have reacted more positively because they had to “come to terms” with something that may have been conflictual for them. “If RTW is going to happen, then you just have to deal with it,” he says. “You have to make the best of a bad situation.”

Although the researchers expected self-affirmation to have a positive effect, they instead found that, among workers for whom RTW was a more distant prospect, self-affirmation had no effect on workers’ levels of burnout or engagement.

When workers’ return was imminent, however, those who self-affirmed actually reported lower levels of job engagement and higher levels of burnout. One possible reason for this surprising finding? Self-affirmation may have interrupted what would have otherwise been a “coming to terms” or rationalization process that they would have naturally engaged in if they had not self-affirmed.

Nor were these effects temporary: In the follow-up survey six weeks later, these tendencies were still present.

Why the research matters: When it comes to the practical implications of the study for managers, Brockner says, “if self-affirmation had made workers feel better about RTW — which is what we expected to find — we would certainly recommend managers to have employees engage in self-affirmation prior to RTW.” But since self-affirmation didn’t help (when the RTW was more distant) and sometimes hurt (when the RTW was more imminent), Brockner says that sometimes “doing nothing” is a better choice. Managers can let workers come to terms with RTW on their own, he adds. “If that’s how things naturally play out, leave well enough alone.”

Adapted from “Work engagement and burnout in anticipation of physically returning to work: The interactive effect of imminence of return and self-affirmation,” by Joel Brockner of Columbia Business School and Marius va