It’s not every day that a country expands its territory by more than one million square kilometers, but this year the US did just that, and extended its maritime boundaries across the Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, the Pacific Ocean, the Arctic Ocean, and the Bering Sea (maritime border between the US and Russia).

But why has the US done this? And why now?

Maritime boundaries and tradition

Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)—which the US has neither signed nor ratified—coastal countries have exclusive rights over the sea column and seabed resources of their exclusive economic zone (EEZ), which extends 200 nautical miles (nm) from their shore. Additionally, countries can claim an extended continental shelf (ECS) of up to 350nm from their coast, where the shallower continental shelf projections extend beyond the EEZ.

Under the UNCLOS, ECS claims require approval from the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) to validate the scientific evidence of the claim. While ECS gives a country jurisdiction over the shelf and seabed resources, it does not give it authority over fisheries operations.

US makes ECS claim

After more than two decades of research and culmination of evidence, the US State Department announced its ECS claim of more than one million square kilometers—four times the size of the UK.

Although the US is not a signatory to the UNCLOS, it does make voluntary trust fund donations to the CLCS and has claimed it may submit its ECS claim to the committee in the future.

As is customary, the fight for natural resources continues driving domestic policy, and the latest US ECS claim is no exception. It is estimated that the Bering Sea in the northern US-Russia maritime border holds around 126 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and more than 24 billion barrels of oil.

US deep-sea mining benefits

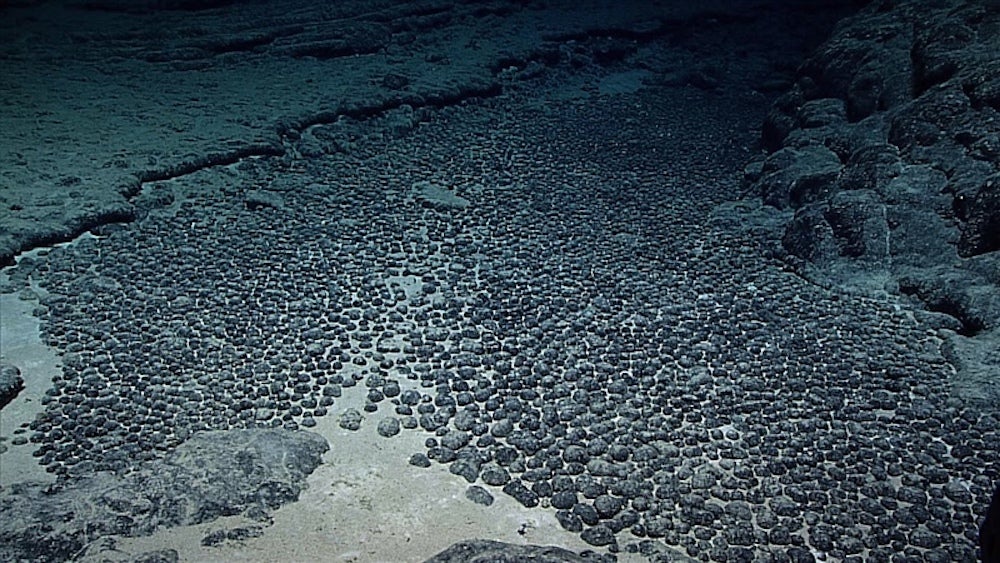

US authorities can also benefit from extended jurisdiction over seabed resources as deep-sea mining gains popularity. Deep-sea mining is the process of retrieving mineral deposits from the deep seabed. While the technology and equipment required for large-scale deep-sea mining is still in the early stages of development, the industry holds great promise. Deep-sea mining companies have found large reserves of critical minerals—including nickel, copper, and rare earth elements—needed for the global energy transition.

Arctic passages and Russian rejection

Beyond the more obvious resource benefits, the US’ ECS claim on the Arctic Ocean may be an early attempt to control future trade routes. As climate change melts the ice caps in the Arctic, scientists estimate that a new Northern Sea trade route could shorten trade routes to the Americas by between 20–50%, avoiding the crowded Panama Canal route. Some estimates claim that Arctic trade routes may divert 2% of global shipping by 2030, reaching 5% by 2050.

Over the last two decades, the US, Denmark, Russia, Canada, and Norway have all made ECS claims in the Arctic Ocean. Given the increasing geopolitical tensions, Russia’s claim over an extensive part of the Arctic is particularly worrisome for US authorities.

Unsurprisingly, Russia equivocally rejected the US’ ECS claim, blaming the US for selectively choosing international regulations “that they find convenient to implement and reject those that impose certain obligations on them.” Arctic disputes will likely escalate as the accessibility to trade routes and seabed resources increases in the coming decade.