The global copper industry is facing a challenge. Population growth, the rise of AI and the global energy transition are all causing demand to boom, with copper used in increasingly popular devices, electric vehicles, power grids and renewable energy infrastructure.

This trend is expected to continue in the coming years. Simultaneously, copper supply is becoming more challenged. Miners are having to go further afield and dig deeper to find resources, and ore quality has been on the decline. As a result, mining companies are future-proofing operations to ensure supply chain stability in the years to come.

In Australia, mining majors such as BHP are ramping up investment into expanding copper projects, focusing on boosting domestic supply chains rather than on further exploration. Uncertainty remains as to whether it will be enough to plug anticipated gaps.

Copper mining in Australia

Australia has a relative abundance of copper, home to around 13% of the world’s supply, with only Chile boasting greater reserves.

However, production has remained at the low end, with GlobalData finding the country was the eighth-largest producer last year. Australia accounted for only 4% of global copper production last year, lagging behind major producers including Chile, Peru, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and China.

“The whole of Australia produces less than the largest mine in the world – the Escondida mine in Chile,” says Piers Montgomery, Australasia base metals supply analyst at commodity research company CRU. “So, it’s not big.”

Still, the country is a well-established mining jurisdiction and companies such as Rio Tinto and Harmony Gold have projects in the pipeline to keep production consistent. BHP has, however, emerged as a forerunner in pursuing copper development, turning particular attention to South Australia as an area of largely untapped resources.

The company’s copper president, Anna Wiley, said at its Copper to the World conference in June that the state is home to 70% of the nation’s supply, with BHP ramping up operations in the area in pursuit of its strategy to support clean energy metals.

“The Australian copper industry is an industry in transition,” says Montgomery. “Queensland is not the production powerhouse it once was, and copper production is now increasingly centred in South Australia.”

While this shift has been happening for some time, it was accelerated by BHP’s A$9.7bn ($6.4bn) purchase of South Australian miner Oz Minerals last year. This deal gave BHP control of Oz’s Prominent Hill and Carrapateena copper and gold mines in South Australia and several copper and nickel projects on the west coast.

The promise of expansion at Olympic Dam

More recently, BHP announced plans to ramp up exploration at its Oak Dam site in the north of the state and expand copper refining facilities at its Olympic Dam mine site near Adelaide.

Of the latter investment, Wiley said it constitutes “one of the most significant investments” into copper manufacturing infrastructure in Australia in decades, with hopes to pave the way for production of more than 500,000tpa of the metal across the state.

Over the past five years, BHP has invested A$1.8bn to improve its Olympic Dam facilities.

BHP began operating in Olympic Dam in 2005, with the site given an estimated life cycle of 40 years. However, in her speech Wiley said BHP “hasn’t found the bottom” of the pit yet, meaning operations could run long beyond this estimation.

Over the past five years, BHP has invested A$1.8bn to improve its Olympic Dam facilities. This investment has paid off, with the site delivering record amounts of copper (322,000t) in the 2024 financial year, up 39% year-on-year.

Despite the optimism these investments imply, the wider copper landscape is still facing uncertainty, and the potential supply shortage could leave even BHP coming up short.

Addressing supply chain challenges

According to Vinneth Bajaj, senior mining analyst at GlobalData, several factors are combined to create copper supply chain challenges.

“Declining ore grades, particularly in major copper-producing regions like Chile, necessitate larger volumes of ore to extract the same amount of copper, increasing production costs and environmental impact,” Bajaj says. “Geopolitical instability, manifested in labour strikes in Peru and the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war, disrupts supply chains and investor confidence.

“Moreover, the scarcity of high-quality copper projects and the extended timeline from discovery to production exacerbate the situation."

Such news does not bode well for an economy at the beginning of its energy transition. The International Energy Agency predicts global copper demand will surge twentyfold by 2040, with existing mines and projects under construction expected to meet only 80% of copper needs by 2030.

“Right now, the supply gap is at a level that we haven’t seen before in terms of absolute tonnes,” says Montgomery. “The issue is that the more we look at the supply gap, the more we’re looking to close it using riskier and less well-defined projects. That, for me, is the worry.

“You’ve also currently got people mining underground at depths coming up to 2km, which is a much more expensive operation.”

Looking beyond Olympic Dam

Globally, mining majors are pursuing more aggressive acquisition strategies to try and come out on top of the copper supply chain. Examples include Glencore’s 2023 bid for Teck Resources’ copper projects and Newmont’s $17.1bn takeover of Newcrest.

In Australia, the race to stake a claim in copper can be seen in BHP’s ongoing attempts to take over Anglo American, so soon after acquiring Oz Minerals. So far, the deal has been rejected, but it showcases a growing preference to expand existing projects, rather than spend money on exploration.

“Something like Olympic Dam, which is an enormous ore body, will run forever and a day,” says Montgomery. “The problem is: a lot of the other mine sites locally are becoming exhausted.”

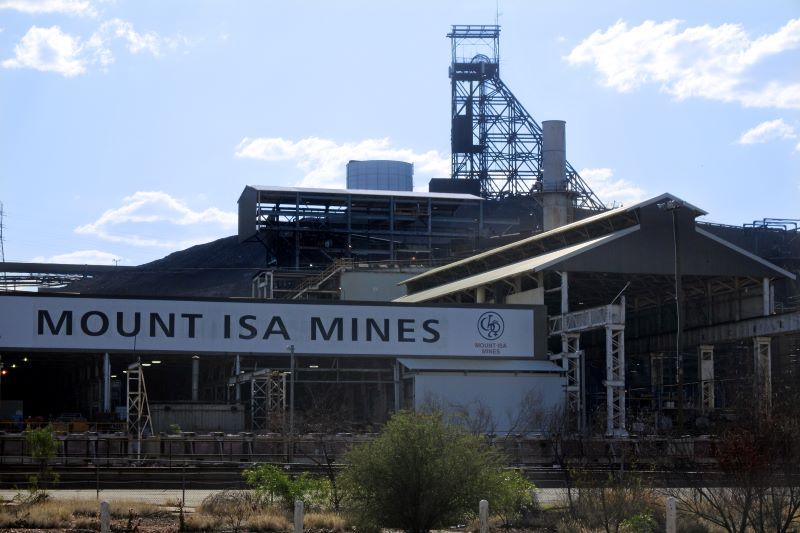

He points to DeGrussa, which closed in the last 18 months, with Glencore’s Mount Isa underground mines to follow next year.

Indeed, analysts at Macquarie forecast BHP's copper output will peak at 1.9 million tonnes (mt) in 2026, then gradually decline to 1.6mt in 2028 – indicative of the wider industry's need to diversify supply chains.

Copper exploration in Australia

“Exploration is a significant challenge because all the low-hanging fruit is gone,” states Montgomery. “We’ve seen a stagnation in exploration spending over the past few years from a number of the top-tier global copper miners.

“We aren’t seeing projects come through at the rate we need for the green energy transition, the demand from electrification and decarbonisation.”

According to Montgomery, Australia currently has three major copper projects in the pipeline, in addition to BHP’s Oak Dam. There’s Harmony Gold’s Eva project in Queensland, Rio Tinto’s Western Australia Winu project, and Rex Minerals’ Hillside project in South Australia.

The nation’s current production capacity is falling short of capitalising its potential.

Crucially, none of the projects is a ‘tier one’ asset, which would be producing more than 100,000tpa of copper. Instead, these are around 40,000tpa–60,000tpa capacity.

“The nation’s current production capacity is falling short of capitalising its potential,” says Bajaj.

“While Australia's copper production is projected to increase to 942,900t by 2030, this represents a modest growth of 140,000t compared to 2023 levels. This incremental expansion pales in comparison to the anticipated global copper supply deficit of an estimated 3.6mt by the same year.

“The huge difference between Australia's projected production and the burgeoning global demand underscores a substantial gap that must be bridged to maximise the country's role in the copper market.”

Boosting copper production in South Australia

One thing is clear – the world needs more copper if it is to achieve a sustainable energy transition.

While BHP has its sights set on South Australia as the key to building the industry and shoring up reserves, there is still some way to go before it can prove itself as a major area of interest, with increased investment needed into tech and skills, as well as industry partnerships and collaboration.

If recent investment activity is anything to go by, however, Australia is still set to carve out a space for itself in the copper landscape – even if only on a domestic level. As for whether the industry can shorten the supply gap, new reserves will have to prove themselves worthy before copper’s safety can be certain.