As a leading producer of graphite, lithium and refined copper, China has an increasingly dominant position in critical mineral supply chains.

With the necessity for these minerals driven by advanced technology and renewable energy capacity, the country’s increasing control both domestically and internationally in regions like Africa raises concerns about diminishing access for Western nations and mining companies.

Jon Harrison, managing director for emerging markets macro strategy at TS Lombard says that over the last seven years, “China has gradually tightened its control” over rare earth and critical minerals, from processing to licensing and regulation, resulting in curtailed foreign company access to mining and other technologies.

China’s share of the critical mineral market

According to data from the International Energy Agency (IEA), China accounts for approximately 80% of natural graphite and 60% of mined magnet rare earths. However, its growing dominance in the world's supply chains is primarily driven by its large refining and processing capabilities.

Amrita Dasgupta, energy and mineral supply chain analyst at the IEA, explains that China is the leading producer of refined copper, lithium, cobalt, graphite and magnet rare earths.

According to Dasgupta, the country produces 99% of battery-grade graphite, more than 60% of lithium chemical, 40% of refined copper, over 80% of refined magnet rare earths and 70% of refined cobalt today, while also dominating the entire graphite anode supply chain end-to-end.

Exemplifying China’s extending control in numerous critical mineral markets is the country's position in the copper, lithium, and nickel markets, respectively.

Shobhan Dhir, IEA critical mineral analyst, notes that China is likely to maintain its dominance in the refined copper market to 2040 while overtaking Peru in the global mined supply of copper.

Similarly, IEA critical minerals and methane analyst Alexandra Hegarty explains that, within the nickel market, China is also expected to maintain its position as a dominant producer of refined metal. She highlights sustained Chinese control internationally, stating: “Although Indonesia currently accounts for 52% of global mined nickel production, in 2023, Chinese companies owned 40% of the production of mined nickel in Indonesia.”

Zooming in on China’s efforts to develop domestic lithium supply, IEA critical minerals analyst Eric Buisson adds that the Chinese share of lithium mining has increased from 6% in 2016 to 17% in 2023, with a prediction that China will overtake Chile as the world’s second-largest lithium producer in the mid-2020s.

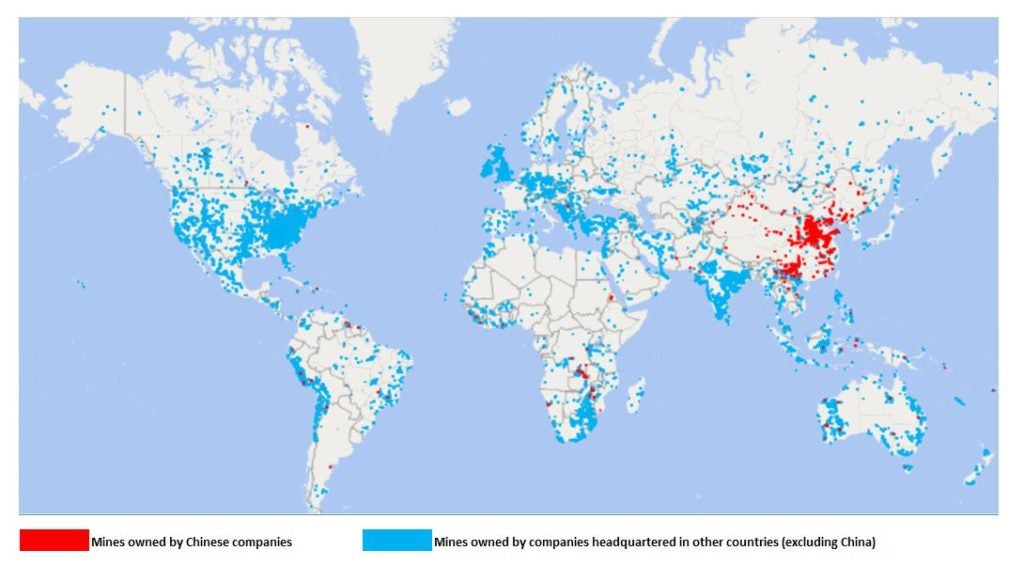

Internal and external investment

“The importance of critical minerals for China has driven an acceleration of Chinese investment into the mining sector, both domestically and internationally,” says Dhir, who adds that Chinese investment into the metal and mining sector related to its Belt and Road initiative reached its highest level in a decade in 2023 at $19.4bn (138bn yuan), representing a 160% increase from 2022.

China has also been significantly investing in and acquiring overseas mines, particularly in Africa, with $10bn invested in the first half of 2023.

“In African nations, the investment has been targeting the creation of new lithium supply chains, where out of the seven lithium assets in Africa that are expected to start production by 2027, five have at least 50% equity ownership by Chinese companies,” say Hegarty and IEA research assistant Yun Young Kim.

What is motivating China’s investment?

“To understand China’s position in the global critical minerals market, it is important to have some background on China’s stronghold in clean energy technology manufacturing,” explains Dasgupta.

Today, China produces two-thirds of the world's electric vehicles (EVs), 85% of battery cell productions, and 90% of cathode and 98% of anode material production capacity globally, while also leading the production of solar panels, wind turbines and hydrogen electrolysers.

Francesca Gregory, senior energy transition analyst at GlobalData, explains that China’s focus on renewable power and battery technology is part of the economic superpower’s strategy to target high-growth industries and fuel the next stage of its economic growth. China is expected to allocate a staggering $6trn to green investment in its 14th Five-Year Plan.

“As part of its strategy to become a green technology pioneer, the country has become a critical mineral monolith,” says Gregory.

According to Gregory, China’s strong position is exemplified in its dominance of lithium and materials in the solar photovoltaic (PV) value chain with key materials such as silicon.

“Lithium’s importance to the energy storage and EV markets has stoked concerns of single-source dependence in the future as geopolitical relations remain fractious globally,” she comments.

“Lithium will remain indispensable in the longer term, with GlobalData estimating that lithium-reliant energy storage projects will reach 54 gigawatt-hours of capacity by 2030 and global annual BEV [battery electric vehicles] sales expected to exceed 36 million by 2030.”

While silicon is not a rare mineral, Gregory highlights that polysilicon production and solar PV manufacturing facilities are heavily concentrated too. She adds: “China alone accounts for an 80% share across the various manufacturing stages of solar panels, including raw material processing and polysilicon production.”

Gregory continues: “In a global energy system that has experienced significant price volatility due to geopolitics, single-source supply risks within technologies such as solar PV and batteries create the potential for new forms of energy dependence.”

Effect on the mining industry

Tom Moerenhout, a research scholar at Columbia School of International Public Affair's Centre on Global Energy Policy, explains that China’s dominance in the processing of critical minerals has allowed it to push down prices to below any matchable level, increasing the rest of the world’s reliance on Chinese exports of these minerals.

With substantial cost advantages and increasing control over critical minerals in Africa, Stewart Worthy, partner at Dorsey & Whitney, who specialises in mining and materials mergers and acquisitions, explains that Western mining companies are now looking at other strategies to remain competitive.

“Western mining companies are now taking a longer view of the energy transition, including by looking to potentially introduce a two-tier pricing system with a premium for sustainably produced metals,” he says. “It remains to be seen whether this comes to fruition, and if so, what – if any – effect it would have on Chinese mining companies’ business.”

US-China Trade War

China’s increasing dominance not only has ramifications for the mining industry but, given the minerals' significance to modern business and technology, also plays a key role in the ongoing China-US trade war.

In response to China’s export-led growth model, in which critical minerals constitute a significant part, the US has increasingly implemented measures to attempt to decouple itself from China’s economy.

TS Lombard’s Jon Harrison says that, while China rarely used to leverage its dominant position in the critical mineral supply chain for geopolitical ends, since 2017, it has “gradually tightened its control over rare earths and other critical minerals, imposing licensing and regulatory requirements, limiting foreign companies’ access to mining, processing and related technology”.

He says that China’s leveraging of dominance in the critical mineral supply chains is in response to US measures to curb China’s access to advanced technologies.

Similarly, Moerenhout notes that, while this plays into the “tit-for-tat games of trade restrictions” between China and the US, its dominance also allows Chinese companies the ability to push down prices and reduce competition of companies outside of China to levels that are economically unsustainable for other businesses to operate at.

Moerenhout adds that the export restrictions have accelerated over the past year, expanding not just from restrictions on the semiconductor industry but also in the battery supply chain and national security supply chains such as those for the valuable semi-metal antimony.