Over 20 years ago, Rwanda suffered a deadly civil war and while the scars of war are still evident and border clashes still occasionally occur, the country has largely been at peace since.

Nevertheless, the African country is still subject to Section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, which covers tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold, all of which Rwanda produces in large quantities. The country is also party to the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) due diligence guidelines.

All of the above legislations, put in simple terms, require companies operating mines or buying minerals from East and Central Africa to perform due diligence and traceability on minerals and mine sites to prove operations do not violate human rights and minerals are not being illegally sold to fund conflicts and other illegal activity.

It is this state of affairs that the Rwanda Mining Association (RMA) has decried as a major inhibiter, suggesting all such systems should be scrapped.

The RMA says these initiatives, which are designed to prevent illegal trade in minerals from East and Central Africa, are expensive, unnecessary, and prohibitive for local miners – 80% of which are small-scale operations.

High-risk environment

Joanne Lebert, executive director of non-governmental organisation IMPACT, says that although Rwanda is not experiencing active conflict, it is a conflict-affected and a high-risk environment because of its neighbouring countries, which include the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

“Therefore, buyers and sellers have to apply OECD due diligence guidance. So, whether or not Rwanda thinks it applies to them is irrelevant, unfortunately,” she adds.

Reuters reported in 2012 that a United Nations (UN) expert panel had discovered traders in Rwanda were profiting from tin, tungsten and tantalum smuggled across the border from mines in the DRC that, the UN said, were helping to fund a rebellion in the country.

However, John Bosco Kanyangoga, a legal and policy advisor for the RMA, vehemently disputes this argument and says Rwanda has been unfairly “lumped in” with its neighbours.

“That [argument] has never been validated and most of the genuine business men and women in Rwanda and their business partners around the world have a contrary opinion,” he says.

“To be honest, this is not fair; how come in other parts of the world trading dynamics of nations are not affected by what happens in neighbouring countries; why should such arguments apply only in Africa?”

Costs of implementation

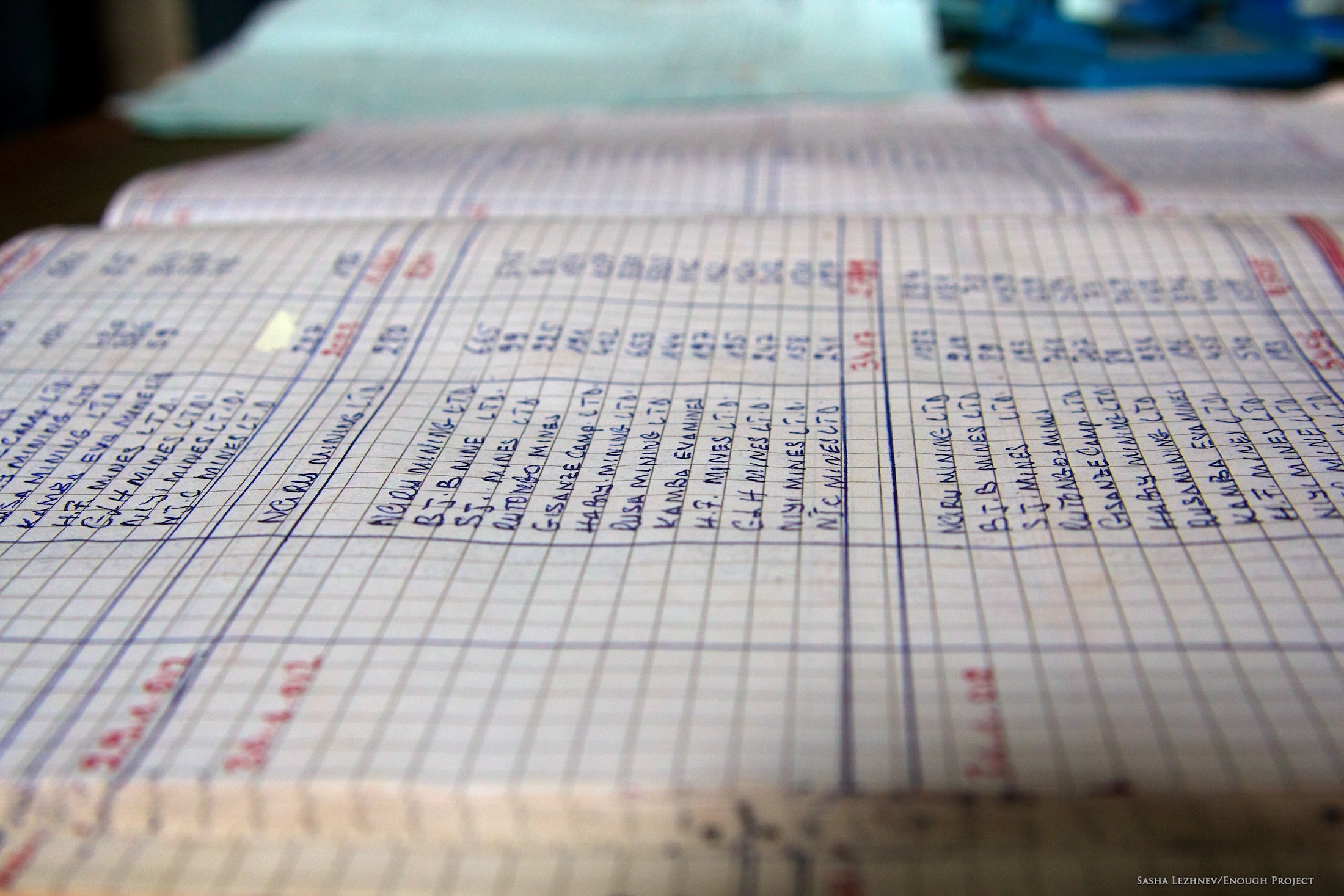

To meet the traceability and due diligence requirements Rwanda implements ITSCI, a programme for responsible supply chain management. It works on the ground via managers deployed at mining concessions that seal, tag and record bags of minerals produced to “efficiently monitor and contain potential illegal dealings”, according to the organisation.

Kay Nimmo from the International Tin Association, who works to implement ITSCI, says due to issues such as poor border control, Rwanda is considered a high-risk region, but ITSCI enables the country to be considered as lower risk by end users. Without it, the Rwandan mining companies and cooperatives would need to apply OECD guidance themselves.

“If ITSCI was not in place, every metal buyer would be expected to visit every mine site on a regular basis – that would be extremely repetitive and not in any way cost efficient,” she adds.

Nevertheless, many, including the RMA, say the cost of implementing ITSCI is “too high”. And, according to Kanyangoga, miners solely foot the bill.

He says the cost depends on the types of minerals being produced, but states that the lowest is “around $130 per tonne and the highest around $180 per tonne”, which is paid to government inspectors. Plus, an additional fee that goes towards ITSCI, which is, for the mineral coltan, for example, a further $1.59/pound ($0.876/kg), he adds.

However, Nimmo says the upstream industry, from mines to smelters, share the costs, with no miner paying ITSCI directly. The fee is partly deducted from their payment by the buyer “as any service such as transport would be,” she explains.

Could costs be reduced?

Working to reduce the cost of the system could be a compromise. Nimmo says that while ITSCI is “constantly investing” in improvement, it is unfortunately not possible to replace field teams walking to mine sites and checking for the presence of children, unusually high production rates, or other potential OECD listed risks.

Though she adds: “We are always open to new ideas to increase efficiency but not at the expense of reducing standards.”

The costs to upstream could reduce if the downstream industry – multinational end product manufacturers – were to contribute more than their current less-than-1% of annual funding to the programme, she adds.

As reported by Rwandan news site The New Times, Francis Gatare, CEO of Rwanda Mines, is advocating to have a cost that is value-based, or that is specific or low enough especially for upstream mining communities.

“There are other options that are being considered and we are continuing to advocate for changes, we are optimistic…but certainly there is a consensus that the cost is not reflective of what it should be,” Gatare noted.

However, Kanyangoga says that reducing the costs alone is not sufficient.

“Whatever costs – low or high – are costs and that is not in the best business interests of the miners and RMA is an association of miners. Remember, this is all in addition to taxes and other production and operational costs,” he says.

Further, he dismisses claims that scrapping ITSCI would put buyers off. “We have to remember that the buyers are not the ones who imposed these systems so they would not mind at all,” he adds.

Does the system work?

A recent detailed assessment by the OECD concluded that the standards of the ITSCI programme are “100% aligned with the 5 Step due diligence recommendations of the OECD’s internationally accepted guidance for good company management, risk assessment and mitigation, auditing and public reporting in responsible minerals supply chains”.

However, some concerns were anonymously raised about the standards and transparency of reporting by ITSCI, such as not publishing baseline assessments about production capacity at mines ascribed tags, which they say makes it hard to verify if the number of tags used correspond to the estimated production for each mine.

Generally slow reporting makes scrutiny hard. For example, member company due diligence reports for 2017 are not yet public, and incident reports for the July-December 2017 period were not published until October 2018.

Karen Hayes, vice president of mines to markets at Pact, an ITSCI implementing partner, says the primary source of reporting information is from the various government agents who collect the mine production, processing and export data and share it with ITSCI. Commercially sensitive information is restricted to companies directly involved in any specific sourcing, and certain information is restricted to members, she adds.

Lebert also believes there should be more transparency around the cost of the system, such as how much is paid per kilo or ton of tagged material, per mineral, per province or country, and who is paying what share of the system.

“ITSCI and their partner Pact claim to be non-profit so this information should be public,” she says. “If these systems are to be sustainable, there has to be transparency on how the costing is calculated and who is paying what and where it is going and how it will be viable over the long term.” She adds that Pact and ITSCI should be more open to healthy competition to keep costs down and options open.

“They are one of the only systems and that near monopoly has been problematic, therefore it is good the government wants to try new things, provided new systems are transparent about costs and sustainability,” she says. “The government and private sector should have a choice of systems and that is something the RMA is likely wanting.”

Furthermore, she adds that the buyers who require due diligence in place should be putting pressure for more granular level detail about costs and should be requesting a more competitive cost structure and more clarity about long-term sustainability, especially as producers start pushing back on costs.

Moving forward to ensure growth

Kanyangoga is unequivocal that if traceability fees are not scrapped, miners will continue to struggle and have their business growth limited.

“And currently the sector is employing many people, so its growth has tremendous social economic development impact,” he says.

Pact and ITSCI maintain that the system is committed to ensuring the livelihoods and security of the 75,000 miners with whom they work.

Thinking more broadly about the wider benefits of such systems, especially in terms of mitigating risk and attracting foreign investment, Sir Richard Shirreff, co-founder and managing partner of Strategia Worldwide, a global risk consultancy that works with the mining industry in Africa, says: “It is really important to have a due diligence process for governments to assure that the risks of a project have been properly thought through.

“I would say that there probably is still a requirement to make sure mining companies are approaching things in a truly sustainable manner and that all stakeholders’ interests are being looked after.”