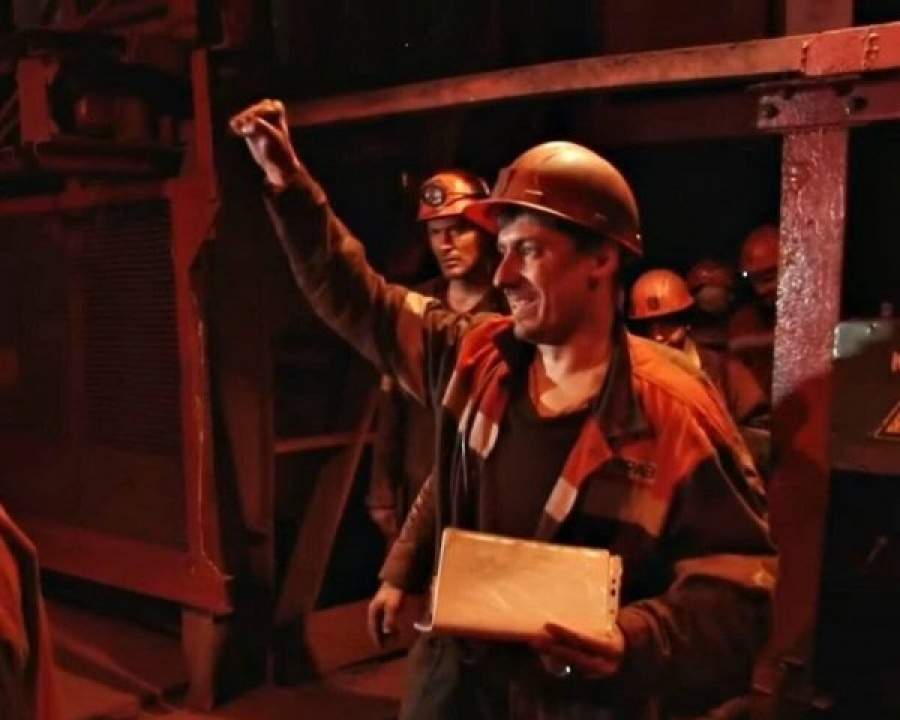

Coal mining in the east of Ukraine has once again ground to a halt, as thousands of workers stopped their duties to protest wage arrears in February. Selidivvugillya, the state-owned mining company, runs four mines in the region but has repeatedly failed to pay its workers.

This is not the first strike to affect eastern Ukraine, which has seen almost continuous union action over the past few years. Strikes started in 2017 were only settled in December when workers were finally paid UAH365m (€10.8m) of missing wages. This situation has been mirrored in western Ukraine, with state-run also Lvivvugillya failing to pay miners in last year, resulting in strikes that were only settled when emergency funding was sought to cover wages.

Discover B2B Marketing That Performs

Combine business intelligence and editorial excellence to reach engaged professionals across 36 leading media platforms.

Ukraine was once the industrial hub of the Soviet Union and produced vast amounts of coal. But today, with military, economic and political complications creating problems, it seems to be struggling to keep its industry alive.

Ukraine has the sixth-largest reserves of coal in the world, and for more than a century has been a major producer and exporter. The bulk of its resource is in the Donetsk coal basin in eastern Ukraine, with a reserve of 101.9 billion tonnes.

While mining was an important industry during Ukraine’s time as part of the Soviet Union, throughout this period, miners were poorly paid and largely ignored by the government. Mining operations themselves were so ineffective that it cost more to produce a tonne of coal than it was actually worth. Then in 1989, miners took the unprecedented step of strike action, starting a movement that continued until 1991 and helped drive Ukraine towards independence with hopes of better pay and conditions.

Ukraine’s wage arrears continue to grow

Today there are about 150 mines operating in Ukraine, of which 90 are state-owned and run by the Ministry of Energy and Coal Industry (MECI). It is these state-run operations that are currently struggling, building up the huge wage arrears that have sparked protests, demonstrations and strikes since 2015. This is particularly evident in the eastern regions of Ukraine, such as the towns of Selidovo and Novogrodovka, where action has been ongoing for years.

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataIn 2016, Victor Trifonov, the local chairman of the Independent Trade Union of Miners of Ukraine in the towns of Selidovo and Novogrodovka, set himself alight at a press conference in an effort to get the attention of the MECI. This came after authorities had failed to act on union demands for the MECI to pay wage arrears, ensure the continuation of mine operations and safeguard jobs. Miners and unions also called for the government to stop purchasing coal from abroad for twice the price of domestically produced coal.

Following this, some wages were paid, but problems have continued and now seem to be escalating. In February, a three-day strike was held by 7,000 Selidivvugillya workers in Selidovo and Novogrodovka, and nine people took part in a hunger strike to demand payment of wage arrears, increases in wages in line with inflation, and investment in health and safety. Furthermore, workers are demanding the return of coal fields they claim were ‘stolen’ from them when they were sold off to private companies.

This action was successful to a point, as the government transferred $13.5m to the company to pay workers in the coal sector across Ukraine. Of this, $3.4m went to Selidivvugillya staff. However, this is only part payment and they are still owed $4.5m. Throughout Ukraine, the mining industry’s general debt is estimated to be $18.7m.

Mining Technology contacted union leaders for comment; however, they have been called in for conversations with the Security Service of Ukraine, so were unavailable.

Separatist complications

The wage arrears and other concerns have built up in the coal mining industry in Ukraine for a number of reasons. Allegations of corruption have been made by many, including Oleksandr Kharchenko, managing director at Energy Industry Research Center in Kiev. He claimed that the money from state-run mines has been redirected, which has been a key cause of the wage arrears.

Others claim that the deep nature of Ukrainian coal operations and low productivity of many mines has made them unprofitable; they have therefore been heavily dependent on government subsidies for years. The level of these subsidies has changed with each government, without great reform to the industry.

Communication failures between the MECI and state-run mining companies and unions have allowed the situation to reach the critical point it is at today.

“We urge Ukrainian Government to re-launch social dialogue with the unions, and take effective measures to solve the problems affecting the coal industry,” said IndustriALL Global Union general secretary Valter Sanches in a letter to the Prime Minister of Ukraine. “We stand in solidarity with our affiliated trade unions and our fellow miners in the Ukraine and support their legitimate demands and necessary legal steps required to protect the rights of workers.”

Political and military upheaval has complicated the situation. In April 2014, pro-Russian separatists formed a militia that took Donetsk and Luhansk out of the Ukrainian Government’s control. In July 2017, they announced that they had founded a new country called Malorossiya, or Little Russia in English.

The four Selidivvugillya mines that have been striking this year lie very close to the eastern border with the People’s Republic of Donetsk, increasing the tension in the region. Many miners are concerned that due to unpaid wages they could not afford to move in an emergency, putting them and their families at risk.

Furthermore, 85 coal mines lie inside this disputed region. The resource-rich area accounted for 57% of production up until 2014, when reports stopped. Only 35 state-run mines are outside of this region, which must continue producing coal for domestic use. It is currently illegal to purchase coal from the separatist regions; however, there are reports that it is being sold to Russian, Polish and other European companies.

Since 2014, Ukraine has engaged in numerous coal import deals to make up for the lost supply created by the loss of territory. The majority of coal has been imported from Russia, which provided 55.7% – $1.2bn worth – between January and October 2017. The country has also begun importing American coal for the first time in its history, in particular anthracite, the price of which America has tripled since 2016. Overall, during the first ten months of 2017, Ukraine spent $2.15bn on coal imports.

With the significant challenges caused by the separatist movements drawing focus, many miners feel ignored by the government. As government officials in Kiev try to limit illegally sold coal and avoid an energy crisis, communication has broken down with the remaining coal miners.

A time for communication

Ukrainian state mines currently employ 51,000 workers, and are the main source of employment in regions such as the Donetsk coal basin. Mine closures over the last few years have already decimated towns and the government does not desire to close more but there is little clarity on how to progress in a profitable and sustainable way.

“The development of state-owned mines is possible in a stable environment, but wages must be paid on time,” said Trade Union of Coal Industry Workers of Ukraine deputy chair Valery Mamchenko. “Last year, UAH2.8bn ($100m) was allocated for the development of the coal industry, including the wage fund, but this year the amount is less than half.”

Without communication with unions and workers, many fear that Ukraine’s coal mining industry will remain stuck in its cycle of non-payment, protests and emergency measures. “It is essential to pay wage arrears in full; stamp out corruption in the industry; appoint managers of enterprises and mines on merit alone; and establish an effective social dialogue with trade unions,” said the Independent Trade Union of Miners of Ukraine president Mychailo Volynets.

The next few years will determine the future of Ukraine’s mining industry; now is the time for the government to focus on and support coal communities. Whether or not mining is to continue to play an important part in Ukraine’s economy and the lives of its citizens, or if it is time for the subsidies to be reduced and new energy industries to be grown, a plan must be made.