The UK has to cut its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by more than 90% over the next 30 years to be consistent with a whole-economy target for net-zero GHG emissions by 2050. Independent advisory the Climate Change Committee (CCC) said in its Sixth Carbon Budget at the end of 2020 that “the impact of current industrial decarbonisation policies is far below what is required for this level of ambition”.

The UK became the first major economy in the world to legislate for net-zero emissions by 2050, back in 2019. Now, the UK Government is tacitly supporting a new deep coal mine in England’s northwest.

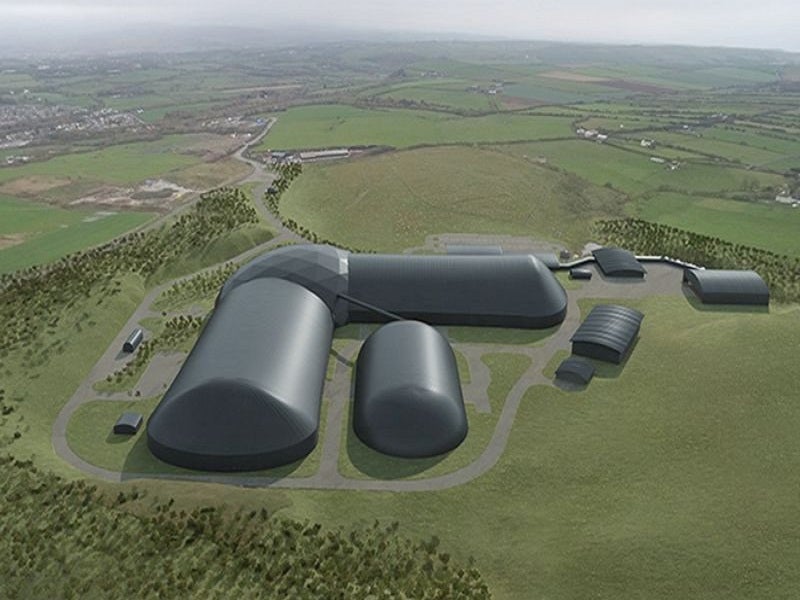

West Cumbria Mining has been developing plans for an underground metallurgical coal mine off the coast of Whitehaven since 2014. Woodhouse Colliery, as it is known, was given the go ahead in October 2020 by Cumbria County Council. The UK Government decided it wouldn’t intervene with the approvals process, leaving the local authority to decide the fate of the major project.

Reviewing the mine’s approval

Cumbria County Council took the decision in February 2021 to return the planning application for Woodhouse Colliery for review, in light of the CCC’s Sixth Carbon Budget recommendations. The report sets out the amount of carbon that can be emitted between 2033 and 2037 if the UK is to meet its target in 2050.

The report’s recommended pathway requires a 78% reduction in UK territorial emissions between 1990 and 2035 – a more significant reduction than had been anticipated in that timeframe.

Lord Deben, chair of the CCC, criticised government ministers for not calling in the mine proposals for further scrutiny as giving a “negative impression of the UK’s climate priorities”. Advisers with the CCC have suggested that the mine going ahead would also undermine the UK’s leadership at COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference, which the UK will host later this year.

Recently, business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng admitted there was “a slight tension between the decision to open this mine and our avowed intention to take coal off the gas grid”. For the government’s part, it distinguishes between coking coal – that used for steelmaking and the material to be sourced from Woodhouse Colliery – and thermal coal, used for electricity generation.

This hasn’t settled the issue. Dr Simon Carr, programme lead for geography at the University of Cumbria, says that opening a new coal mine is “completely incompatible with the UK’s climate pledges”.

“If this goes ahead, each job that will be created has been estimated to result in 18,000 tonnes of CO2 emissions per year,” Carr explains. “Given that the UK average carbon footprint is between five and 10 tonnes per year, you can perhaps see why anyone involved in climate science is so concerned about this.”

Mark Jenkinson, a former employee of British Steel and now the Conservative Member of Parliament for Workington, a Cumbrian constituency close to the site of Woodhouse Colliery, believes the mine proposals can be reconciled with the UK’s decarbonisation commitments: “The new mine delivers net-positive emissions for the UK and is absolutely aligned with our ambitious, world-leading net-zero targets.

“I am struck by some of the NIMBY arguments from climate extremists that somehow, it’s somebody else’s problem if we mine it in the US and ship it to the UK or Germany… We cannot pat ourselves on the back for a job well done on hitting net-zero in 2035 if all we’ve done is offshore our commitments.”

West Cumbria Mining CEO Mark Kirkbride, commenting on the decision to review the approval, said: “The construction of every wind turbine depends upon the availability of high-quality steel, which in turn requires large quantities of metallurgical coal for its manufacture. This status quo will not change within foreseeable timelines.

“The Committee on Climate Change Report contemplates the construction of vast numbers of wind turbines, which will require steel from UK and European steelmakers. Metallurgical coal for these producers is currently imported over long distances from the US, Australia, and Russia.”

A contentious local issue

Advocates of Woodhouse Colliery tout its potential as an economic boost to the coastal town of Whitehaven and the wider West Cumbria region, which has historically been a deprived part of England. West Cumbria Mining proposes to create more than 500 permanent roles working at the mine and forecasts more than 1,500 indirect jobs in the local supply chain.

Carr disagrees: “The economic argument that is being pushed by the MPs and the proponents of the scheme is also disingenuous and plays upon the long-term challenges that West Cumbria faces in terms of economic hardship and social deprivation. At best, this mine would employ staff for perhaps 20-25 years, which is just one generation of a workforce.

“West Cumbria desperately needs investment to reverse long term economic and social decline, and to offer opportunities to develop and employ a skilled workforce that encourages people to stay in the region and even migrate into the region.

“The assorted initiatives to develop a green energy platform are just the types of innovations that the region needs. These are the sort of industries that offer hope and a long-term future for Cumbria, not the frankly Victorian dinosaur that Woodhouse represents.”

Is there a future beyond coking coal?

The mine’s raison d’etre – producing metallurgical coal for the UK’s steel industry as well as exporting large quantities abroad – has been called into question as lower carbon methods of steelmaking gain support.

The potential of hydrogen-based steelmaking has recently been explored by the European Parliament, and UK think tank Common Wealth has advocated a green strategy for the UK’s steel industry that makes use of hydrogen and carbon capture technologies to decarbonise the process.

Supporters of the mine suggest that there is currently no viable alternative to coking coal for steelmaking, a view shared by Jenkinson.

“We should absolutely invest, and heavily, in decarbonisation of steelmaking, and indeed other industries,” the MP says.

“But we have to stop talking about coking coal as though it’s fuel and recognise that it is an important chemical element for many industrial processes. There remains no alternative to coking coal, viable or otherwise. A lot of the talk is around hydrogen as a reductant, but this is only part of the process.”

In a House of Commons debate titled ‘The Future of Coal in the UK’, Jenkinson said that: “Counter-intuitively, part of the route to net-zero is to bring back some of our carbon footprint that we’ve offshored by importing from countries that often have dubious environmental protections.”

COP26 has been described as the world’s “last best chance” to avert climate catastrophe by US climate envoy John Kerry. Woodhouse Colliery may well collide with the UK Government’s intention to be a world leader on battling climate change.

Jenkinson’s plea in the House of Commons to “not let the perfect be the enemy of the good” when it comes to net-zero by 2050 may not sit well with those who see a coal mine as fundamentally irreconcilable with decarbonisation and averting the severe effects of climate change.

Or, as Carr puts it: “This mine would be about as effective at supporting the UK’s leadership on climate change as Dominic Cummings’ trip to Barnard Castle was at supporting nationwide support for the Covid-19 lockdowns.”