In October 2020, China effected a ban on imports of Australian coal. Australian exports account for 58% of the global seaborne trade or metallurgical coal, essential to primary steelmaking. China is a steelmaking hub, accounting for 57% of world steel production in 2020.

The ban was expected to impact the economies of both countries adversely. Indeed, for China, since it enacted the ban, every million tonnes of coal used in its steel mills has cost more than $400m, compared with around $250m paid by everywhere else.

However, both countries have also adapted effectively. China has shored up its supplies from extensive domestic production increases and larger imports from other coal-producing powers such as Indonesia. Australia has also partially offset its losses by increased shipments to India, South Korea, Taiwan, and Japan.

With little political will on either side so far towards a thawing of relations, it can be expected that the import ban could continue through into 2023. Whether this will prove detrimental to both countries is up for question; however, due to coal’s abundance and willing buyers, demand will likely remain high enough to avoid forcing the hand of either state.

Import/export

China and Australia have had a long relationship with coal. Australia has been one of China’s main trading partners in coking coal. Before the ban, over January-August 2020, Australia exported 38.6 million tonnes of thermal coal and 31.6 million tonnes of metallurgical coal to China, up from 4.6 million tonnes and 8.5 million tonnes year on year respectively, Platts Analytics said.

In October 2020, however, Beijing issued a verbal communication to state-owned energy companies and steel mills to immediately stop importing Australian coal. Relations had soured after Australia called for an independent investigation into the initial coronavirus outbreak in China, with Prime Minister Scott Morrison suggesting that WHO needed tough, “weapons inspector” powers to investigate the cause of the outbreak.

As well as banning coal imports, China banned the import of beef from four Australian beef processing firms, instituted an 80% tariff on barley imports from Australia, and imposed “anti-dumping” tariffs ranging from 107.1% to 212.1% on wine imported from Australia.

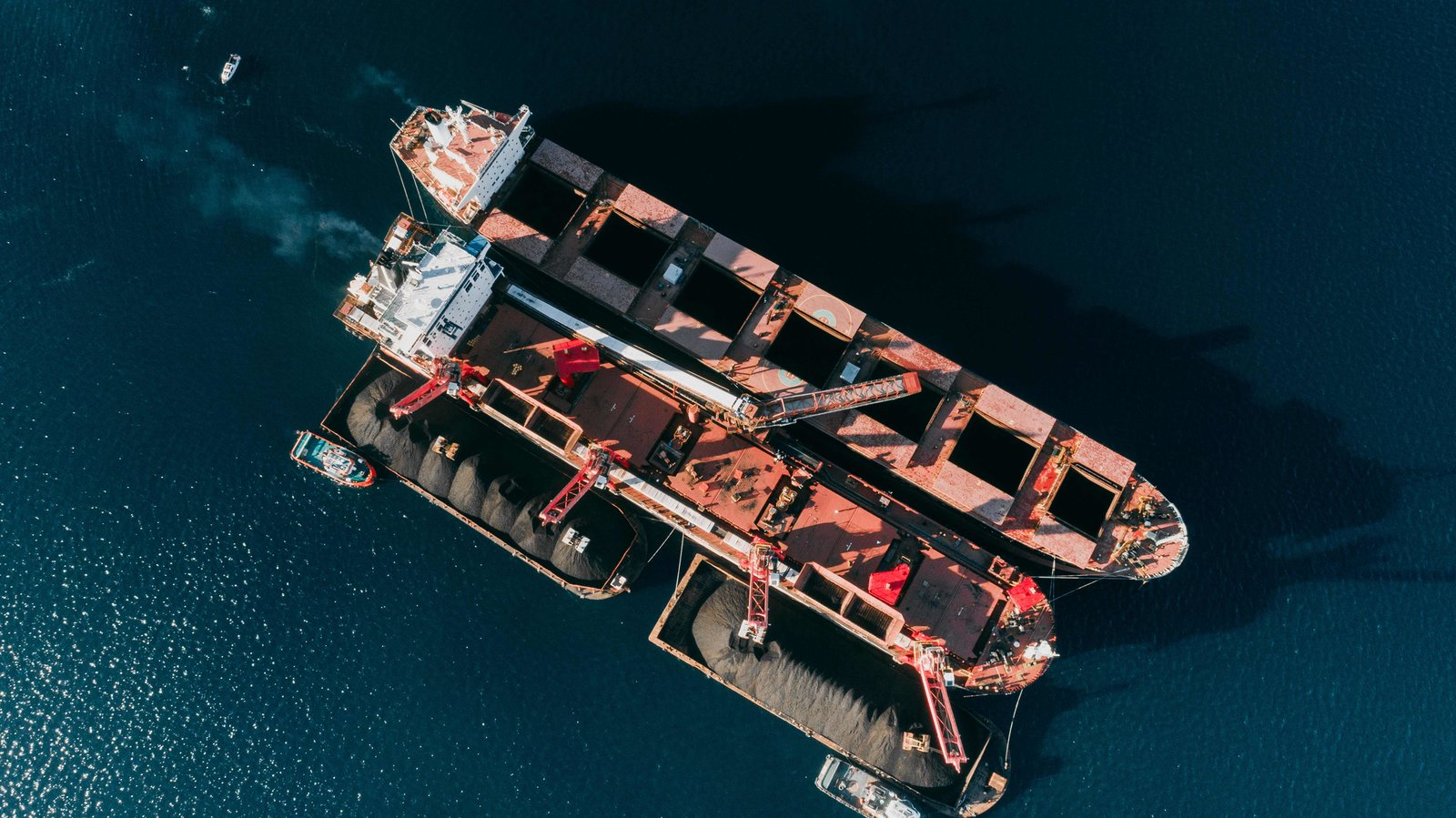

The ban had immediate impacts on both countries, with a queue of 46 ships carrying around five million tonnes of Australian coal forming off the Chinese coast by December. The price for Australian coal plunged while prices inside China jumped, with a close gap of $85 per tonne opening between the two.

A look ahead

Since the ban, there has been little movement on either nation’s part to thaw relations. In March 2021, it was reported that the Australian ambassador to China, Graham Fletcher, commented that China is a “vindictive” and “unreliable” trading partner as it was revealed that most Australian exports to China, including coal, wine, barley, cotton, lobsters, and wood, suffered steep declines for almost a year.

Since the ban, both countries have made an increased effort to alleviate the ban’s impact. For the Australian coal industry, new windows of opportunities have opened up. Several other Asian markets, namely India, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, have seen sharp upticks in coal imports from Australia.

Shipments from Australia to India have grown five-fold in the first three quarters of 2021, rising 503% year on year to 16.5 million tonnes in January-September.

“Australian producers have been able to cushion any impact of the trade dispute by diversifying their export customer base,” said Matthew Boyle, global coal markets senior analyst at S&P Global Platts Analytics.

As a result, while the Chinese ban has significantly impacted Australian coal’s trade flow, the impact on overall volumes has been negligible. Platts Analytics expects Australia’s thermal coal exports in 2021 to fall only 2.7% year on year, to 198.2 million tonnes, and is expected to dip 1.1% year on year, to 196 million tonnes, in 2022.

While China’s appetite for coal has remained high, it has turned to other producers to fill its import gap. China has seen increased imports from coal producers such as Indonesia, Russia, and South Africa. China has also extensively expanded its own coal production to produce 220 million tonnes a year of extra coal, a 6% rise from last year.

Phase down, not phase out

The increase in China’s coal production comes as India, supported by Beijing and other coal-dependent developing nations, brokered a last-minute amendment at the COP26 climate talks in Glasgow, Scotland.

Due to the pressure of these coal-producing powers, the final wording of the accord was changed from “phase out” to “phase down”. Despite this resistance, over the next two decades, the use of coal globally is expected to plummet.

China announced its position to phase down coal usage by 2026, and despite plans to build more coal-fired plants, it has plans to be carbon neutral by 2060, with emissions peaking by 2030.

Doing so, China’s reliance on imported coal will fall significantly, meaning their reliance on imports from coal producers would fall regardless of any improvements to relationships with nations such as Australia. Therefore, it can be expected that the trading partnership will remain in a nadir for years to come, unlikely to again reach the levels seen only two years ago.

For Australia, the position of policymakers so far has been a rejection of a complete phase-out under the belief that emission reductions are possible alongside maintaining Australia’s highly developed resource sector.

Richard Denniss, the chief economist at The Australian Institute, has argued that the Australian position is to maximise profits until complete phase-out occurs: “What we are doing is trying to maximise profits in the endgame. That’s why there is a rush to approve new coal mines. We know that in 30 years, no one will be buying coal. But if we flood the market and push the price down, we can still sell some for the next 15 years.”

Australia is likely to continue to have willing buyers in the East Asian market for the foreseeable future. Therefore, looking ahead into 2022, it seems likely that Australia and China will continue to seek alternative trade partners to meet their individual requirements.