The Amazon rainforest in South America has large quantities of copper, tin, nickel, bauxite, manganese, iron ore and gold, making it attractive to mining companies all around the world. But as the governments of the eight countries that cross the Amazon eagerly try to capitalise on this wealth, concern is growing over the deforestation caused by, amongst other things, mining.

Until recently, mining operations were thought to have only a small comparative impact upon the rainforest, which covers 40% of South America. Estimates previously put the figure at just 1%-2%; however, a new study published by researchers at the University of Vermont (UVM) is as much as ten times that. This is, in part, because for the first time, the researchers looked at the overall impact of all mining operations, and the results are cause for grave concern.

The Amazon rainforest is of great global importance, with just one if its roles being as a carbon sink that absorbs 2.2 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide a year. Deforestation has already had a massive impact on this, the biggest rainforest in the world, with only 80% of the original landmass remaining. Since the 1970s, more than 1.4 million hectares of forest have been cleared, predominantly due to the logging trade, conversion to cattle pastures and agricultural infrastructure.

The hidden impact of mining

Published in Nature Communications, the Mining drives extensive deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon report examines the broader effects of an entire mining operation, as opposed to just the area cleared for the pit. “This topic has received little attention because mining is often considered a small-scale cause of deforestation compared to other land uses,” explains Laura Sonter, lecturer at the UVM Gund Institute for Environment and lead author of the paper. “Mines take up less than 1% of the total land area, compared to pasture (60%-70%), agriculture (20%) and logging (2%-3%). But we found that mining was often the root cause of these other sources of deforestation.”

Over the past decade, the rising price of gold has led to a new rush to mine in the Amazon and increased illegal mining operations in Peru, Columbia and Brazil. In Peru alone, at least 64,000 acres has been stripped for gold mining, much of which is illegal. Deforestation for mining purposes, especially illegal operations, is more complete than that caused by the logging trade, for example, as not only is the forest burned down, stripping away the earth and making regrowth much harder, but also rivers and streams often become contaminated by mining waste such as mercury.

But whilst governments do fight the deforestation caused by illegal mining, operations which are relatively centralised to the mining area, they also welcome large legitimate mining operations with infrastructure that stretches far beyond the pit.

“We assessed both the deforestation within mining leases and indirectly occurring outside them throughout the world’s largest remaining tropical rainforest – the Brazilian Amazon,” says Sonter. “We found off-lease impacts extended 70km from mining leases to cause 12 times more deforestation off-lease than within.”

Using satellite imagery, Sonter and her team mapped the 50 largest mining sites in the Amazon over ten years. During this time, they found that 11,670km² of forest was lost to mining activities and surrounding infrastructure in Brazil alone. “In total, mining-induced deforestation caused 9% of all Amazon deforestation during the decade between 2005 and 2015. This is much more forest loss than we previously thought the mining industry caused and has huge impacts on native biodiversity, carbon storage and climate regulation, as well as having serious social and cultural implications for the people who live in those areas.

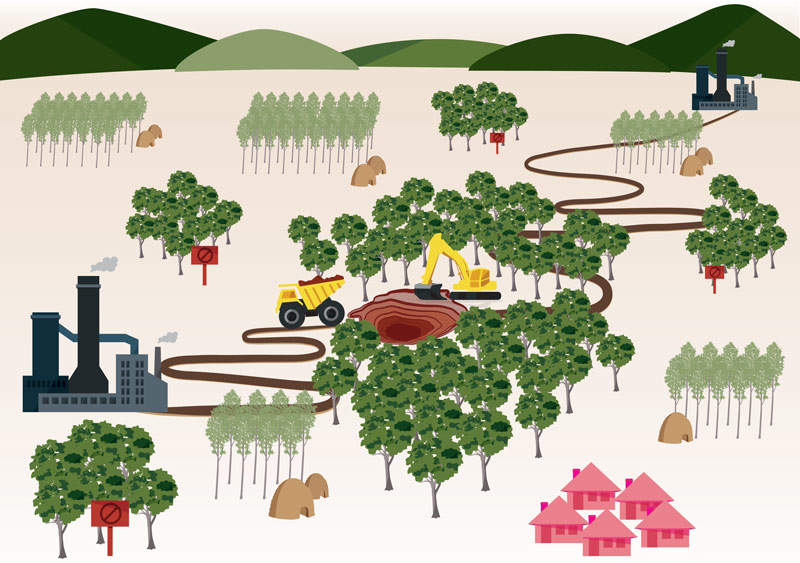

“A range of different factors cause mining-induced deforestation,” Sonter explains. “For example, establishing a new mining operation in a region requires require a lot of extra infrastructure, such as roads and railways to transport the mined ore. Building roads, in turn, provides new access to areas that may have been inaccessible to farmers in the past.”

Protecting the Brazilian rainforest

The study is likely to bolster the argument for stricter environmental regulations in Brazil in particular. Current regulations are limited to actual mining, but as mines provide jobs communities grow, as does the demand for meat and fresh produce in the area. However, at present, forest land cleared to provide roads, worker housing, and associated activities such as agriculture is not considered in the licensing process.

Mining companies are keen to expand into the Amazon, and the Brazilian Government aims to facilitate this, as the study claims that “throughout Brazil, mining leases, concessions, and exploration permits cover 1.65 million km² of land, of which 60% is located in the Amazon forest”.

In 2017, Brazil’s President Michel Temer tried to abolish the national reserve status of the 4.6 million hectare Renca preserve by presidential decree. This would have opened up the land for mining, particularly for two Canadian companies, but protests were widespread and a federal judge annulled the move. However, the Brazilian Union’s General Advocate is planning to appeal the decision.

Efforts to decrease deforestation are underway, and the INPE (Brazil’s space agency) recently found that the rate of deforestation in Brazil decreased by 6,624km² between August 2016 and July 2017. “The result indicates a decrease of 16% compared to 2016, the year that we determined 7,893km², and also a decrease of 76% compared to that recorded in 2004, the year the Federal Government launched the Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation Amazon, currently coordinated by the Ministry of Environment,” the INPE said.

But Sonter is quick to remind us that this is a relatively small success, saying that “while deforestation declined between August 2016 and July 2017, it was still higher than rates during the five years preceding (2011 to 2015)”. “To slow deforestation and conserve Amazon forests,” she says, “we need to understand and address the remaining sources of forest loss.”

Whilst efforts are to be encouraged, whether or not deforestation has already made irreparable damage to the Amazon is unclear, that “will depend on the strength of Brazil’s environmental policies and other economic factors”, says Sonter. “A step in the right direction would be to systematically incorporate indirect deforestation into mining environmental impact assessments and mitigation requirements.”

The Amazon is not just rich in minerals and opportunities, it is a vital carbon store as well as being home to indigenous peoples, animals and plants, many of which have extraordinary medicinal qualities, and as such, it must be protected. As mining companies seek to expand into the wilds of the forest, we must ensure this is done in a sustainable fashion which takes into account the environmental impact of the entire operation.

“We hope the mining industry will take responsibility of their environmental footprint to assess and mitigate the full extent of deforestation related to their activities,” says Sonter.